By David Stockman

David Stockman's Corner

Committee for the Republic & http://www.lewrockwell.com

Washington DC January 20, 2015

My humble thesis tonight is that the entire 20th Century was a giant mistake.

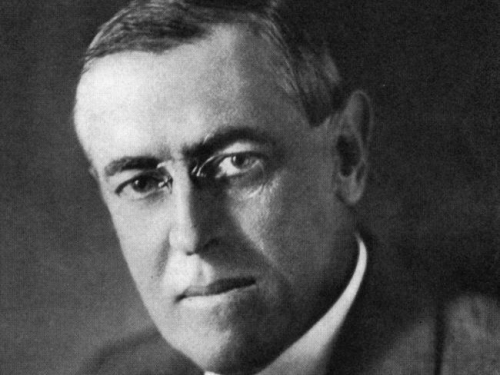

And that you can put the blame for this monumental error squarely on Thomas Woodrow Wilson——-a megalomaniacal madman who was the very worst President in American history……..well, except for the last two.

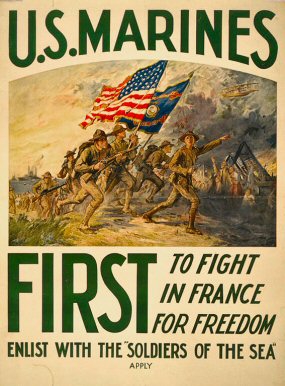

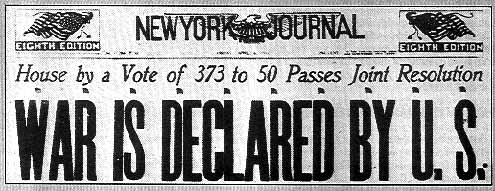

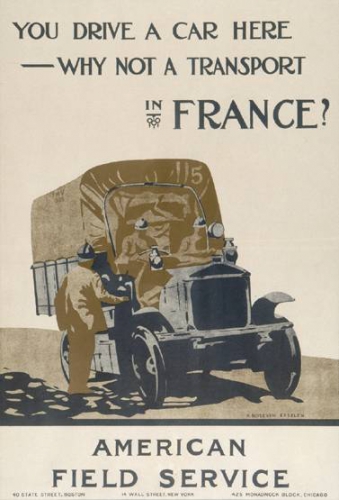

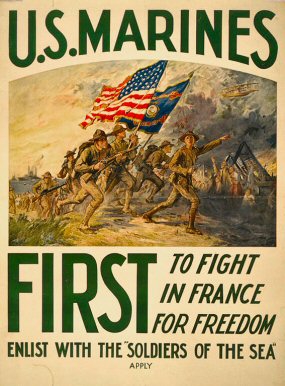

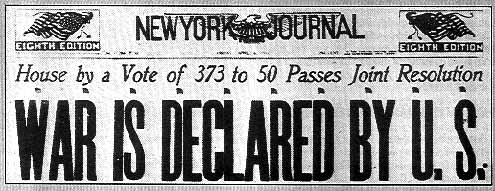

His unforgiveable error was to put the United States into the Great War for utterly no good reason of national interest. The European war posed not an iota of threat to the safety and security of the citizens of Lincoln NE, or Worcester MA or Sacramento CA. In that respect, Wilson’s putative defense of “freedom of the seas” and the rights of neutrals was an empty shibboleth; his call to make the world safe for democracy, a preposterous pipe dream.

Actually, his thinly veiled reason for plunging the US into the cauldron of the Great War was to obtain a seat at the peace conference table——so that he could remake the world in response to god’s calling.

But this was a world about which he was blatantly ignorant; a task for which he was temperamentally unsuited; and an utter chimera based on 14 points that were so abstractly devoid of substance as to constitute mental play dough.

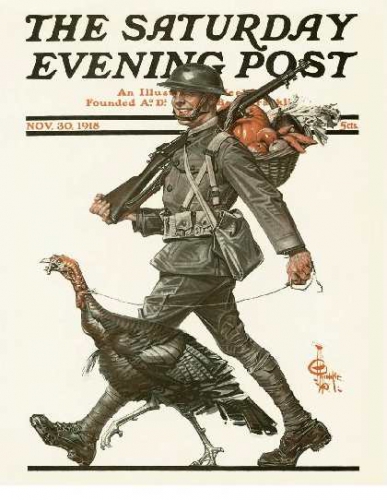

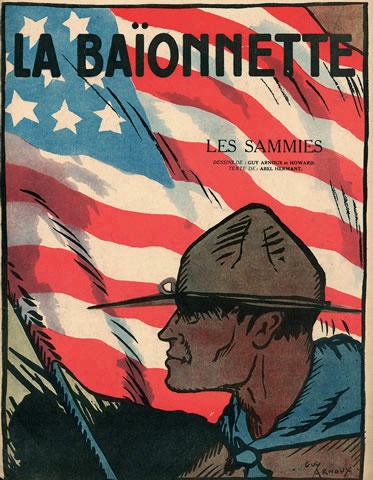

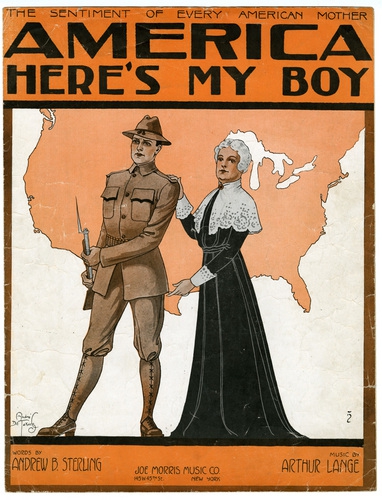

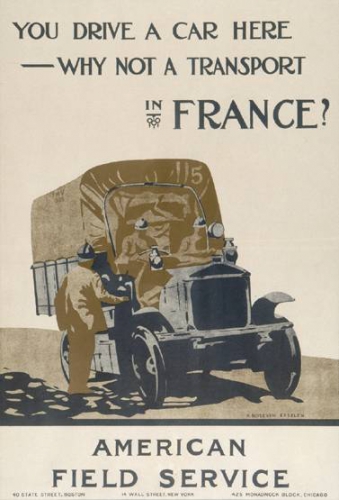

Or, as his alter-ego and sycophant, Colonel House, put it: Intervention positioned Wilson to play “The noblest part that has ever come to the son of man”. America thus plunged into Europe’s carnage, and forevermore shed its century-long Republican tradition of anti-militarism and non-intervention in the quarrels of the Old World.

Needless to say, there was absolutely nothing noble that came of Wilson’s intervention. It led to a peace of vengeful victors, triumphant nationalists and avaricious imperialists—-when the war would have otherwise ended in a bedraggled peace of mutually exhausted bankrupts and discredited war parties on both sides.

By so altering the course of history, Wilson’s war bankrupted Europe and midwifed 20th century totalitarianism in Russia and Germany.

By so altering the course of history, Wilson’s war bankrupted Europe and midwifed 20th century totalitarianism in Russia and Germany.

These developments, in turn, eventually led to the Great Depression, the Welfare State and Keynesian economics, World War II, the holocaust, the Cold War, the permanent Warfare State and its military-industrial complex.

They also spawned Nixon’s 1971 destruction of sound money, Reagan’s failure to tame Big Government and Greenspan’s destructive cult of monetary central planning.

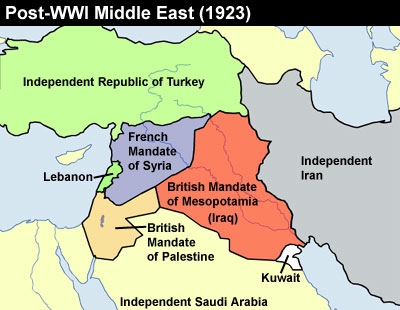

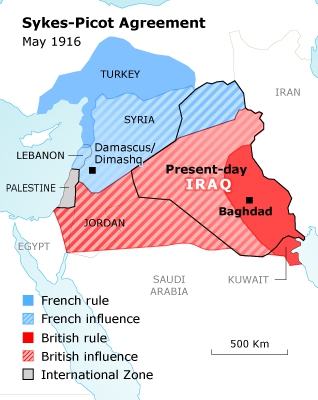

So, too, flowed the Bush’s wars of intervention and occupation, their fatal blow to the failed states in the lands of Islam foolishly created by the imperialist map-makers at Versailles and the resulting endless waves of blowback and terrorism now afflicting the world.

And not the least of the ills begotten in Wilson’s war is the modern rogue regime of central bank money printing, and the Bernanke-Yellen plague of bubble economics which never stops showering the 1% with the monumental windfalls from central bank enabled speculation.

Consider the building blocks of that lamentable edifice.

First, had the war ended in 1917 by a mutual withdrawal from the utterly stalemated trenches of the Western Front, as it was destined to, there would have been no disastrous summer offensive by the Kerensky government, or subsequent massive mutiny in Petrograd that enabled Lenin’s flukish seizure of power in November. That is, the 20th century would not have been saddled with a Stalinist nightmare or with a Soviet state that poisoned the peace of nations for 75 years, while the nuclear sword of Damocles hung over the planet.

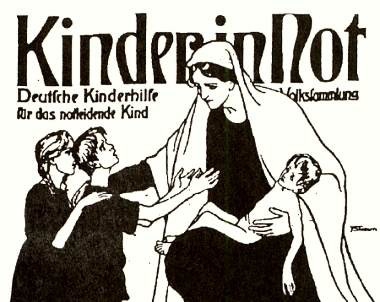

Likewise, there would have been no abomination known as the Versailles peace treaty; no “stab in the back” legends owing to the Weimar government’s forced signing of the “war guilt” clause; no continuance of England’s brutal post-armistice blockade that delivered Germany’s women and children into starvation and death and left a demobilized 3-million man army destitute, bitter and on a permanent political rampage of vengeance.

So too, there would have been no acquiescence in the dismemberment of Germany and the spreading of its parts and pieces to Poland, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, France, Austria and Italy—–with the consequent revanchist agitation that nourished the Nazi’s with patriotic public support in the rump of the fatherland.

Nor would there have materialized the French occupation of the Ruhr and the war reparations crisis that led to the destruction of the German middle class in the 1923 hyperinflation; and, finally, the history books would have never recorded the Hitlerian ascent to power and all the evils that flowed thereupon.

In short, on the approximate 100th anniversary of Sarajevo, the world has been turned upside down.

The war of victors made possible by Woodrow Wilson destroyed the liberal international economic order—that is, honest money, relatively free trade, rising international capital flows and rapidly growing global economic integration—-which had blossomed during the 40-year span between 1870 and 1914.

That golden age had brought rising living standards, stable prices, massive capital investment, prolific technological progress and pacific relations among the major nations——a condition that was never equaled, either before or since.

Now, owing to Wilson’s fetid patrimony, we have the opposite: A world of the Warfare State, the Welfare State, Central Bank omnipotence and a crushing burden of private and public debts. That is, a thoroughgoing statist regime that is fundamentally inimical to capitalist prosperity, free market governance of economic life and the flourishing of private liberty and constitutional safeguards against the encroachments of the state.

Now, owing to Wilson’s fetid patrimony, we have the opposite: A world of the Warfare State, the Welfare State, Central Bank omnipotence and a crushing burden of private and public debts. That is, a thoroughgoing statist regime that is fundamentally inimical to capitalist prosperity, free market governance of economic life and the flourishing of private liberty and constitutional safeguards against the encroachments of the state.

So Wilson has a lot to answer for—-and my allotted 30 minutes can hardly accommodate the full extent of the indictment. But let me try to summarize his own “war guilt” in eight major propositions——a couple of which my give rise to a disagreement or two.

Proposition #1: Starting with the generic context——the Great War was about nothing worth dying for and engaged no recognizable principle of human betterment. There were many blackish hats, but no white ones.

Instead, it was an avoidable calamity issuing from a cacophony of political incompetence, cowardice, avarice and tomfoolery.

Blame the bombastic and impetuous Kaiser Wilhelm for setting the stage with his foolish dismissal of Bismarck in 1890, failure to renew the Russian reinsurance treaty shortly thereafter and his quixotic build-up of the German Navy after the turn of the century.

Blame the French for lashing themselves to a war declaration that could be triggered by the intrigues of a decadent court in St. Petersburg where the Czar still claimed divine rights and the Czarina ruled behind the scenes on the hideous advice of Rasputin.

Likewise, censure Russia’s foreign minister Sazonov for his delusions of greater Slavic grandeur that had encouraged Serbia’s provocations after Sarajevo; and castigate the doddering emperor Franz Joseph for hanging onto power into his 67th year on the throne and thereby leaving his crumbling empire vulnerable to the suicidal impulses of General Conrad’s war party.

So too, indict the duplicitous German Chancellor, Bethmann-Hollweg, for allowing the Austrians to believe that the Kaiser endorsed their declaration of war on Serbia; and pillory Winston Churchill and London’s war party for failing to recognize that the Schlieffen Plan’s invasion through Belgium was no threat to England, but a unavoidable German defense against a two-front war.

But after all that—- most especially don’t talk about the defense of democracy, the vindication of liberalism or the thwarting of Prussian autocracy and militarism.

The British War party led by the likes of Churchill and Kitchener was all about the glory of empire, not the vindication of democracy; France’ principal war aim was the revanchist drive to recover Alsace-Lorrain—–mainly a German speaking territory for 600 years until it was conquered by Louis XIV.

In any event, German autocracy was already on its last leg as betokened by the arrival of universal social insurance and the election of a socialist-liberal majority in the Reichstag on the eve of the war; and the Austro-Hungarian, Balkan and Ottoman goulash of nationalities, respectively, would have erupted in interminable regional conflicts, regardless of who won the Great War.

In short, nothing of principle or higher morality was at stake in the outcome.

Proposition # 2: The war posed no national security threat whatsoever to the US. Presumably, of course, the danger was not the Entente powers—but Germany and its allies.

But how so? After the Schlieffen Plan offensive failed on September 11, 1914, the German Army became incarcerated in a bloody, bankrupting, two-front land war that ensured its inexorable demise. Likewise, after the battle of Jutland in May 1916, the great German surface fleet was bottled up in its homeports—-an inert flotilla of steel that posed no threat to the American coast 4,000 miles away.

As for the rest of the central powers, the Ottoman and Hapsburg empires already had an appointment with the dustbin of history. Need we even bother with the fourth member—-that is, Bulgaria?

Proposition #3: Wilson’s pretexts for war on Germany—–submarine warfare and the Zimmerman telegram—-are not half what they are cracked-up to be by Warfare State historians.

As to the so-called freedom of the seas and neutral shipping rights, the story is blatantly simple. In November 1914, England declared the North Sea to be a “war zone”; threatened neutral shipping with deadly sea mines; declared that anything which could conceivably be of use to the German army—directly or indirectly—-to be contraband that would be seized or destroyed; and announced that the resulting blockade of German ports was designed to starve it into submission.

A few months later, Germany announced its submarine warfare policy designed to the stem the flow of food, raw materials and armaments to England in retaliation. It was the desperate antidote of a land power to England’s crushing sea-borne blockade.

Accordingly, there existed a state of total warfare in the northern European waters—-and the traditional “rights” of neutrals were irrelevant and disregarded by both sides. In arming merchantmen and stowing munitions on passenger liners, England was hypocritical and utterly cavalier about the resulting mortal danger to innocent civilians—–as exemplified by the 4.3 million rifle cartridges and hundreds of tons of other munitions carried in the hull of the Lusitania.

Likewise, German resort to so-called “unrestricted submarine warfare” in February 1917 was brutal and stupid, but came in response to massive domestic political pressure during what was known as the “turnip winter” in Germany. By then, the country was starving from the English blockade—literally.

Before he resigned on principle in June 1915, Secretary William Jennings Bryan got it right. Had he been less diplomatic he would have said never should American boys be crucified on the cross of Cunard liner state room so that a few thousand wealthy plutocrat could exercise a putative “right” to wallow in luxury while knowingly cruising into in harm’s way.

As to the Zimmerman telegram, it was never delivered to Mexico, but was sent from Berlin as an internal diplomatic communique to the German ambassador in Washington, who had labored mightily to keep his country out of war with the US, and was intercepted by British intelligence, which sat on it for more than a month waiting for an opportune moment to incite America into war hysteria.

In fact, this so-called bombshell was actually just an internal foreign ministry rumination about a possible plan to approach the Mexican president regarding an alliance in the event that the US first went to war with Germany.

Why is this surprising or a casus belli? Did not the entente bribe Italy into the war with promises of large chunks of Austria? Did not the hapless Rumanians finally join the entente when they were promised Transylvania? Did not the Greeks bargain endlessly over the Turkish territories they were to be awarded for joining the allies? Did not Lawrence of Arabia bribe the Sherif of Mecca with the promise of vast Arabian lands to be extracted from the Turks?

Why, then, would the German’s—-if at war with the USA—- not promise the return of Texas?

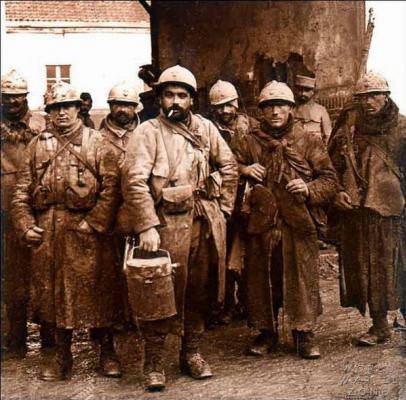

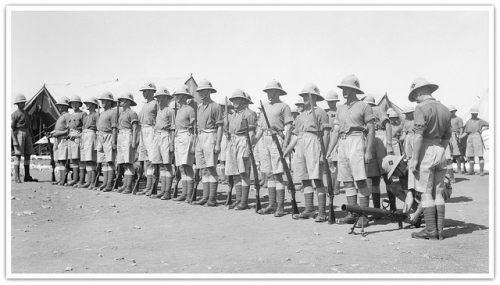

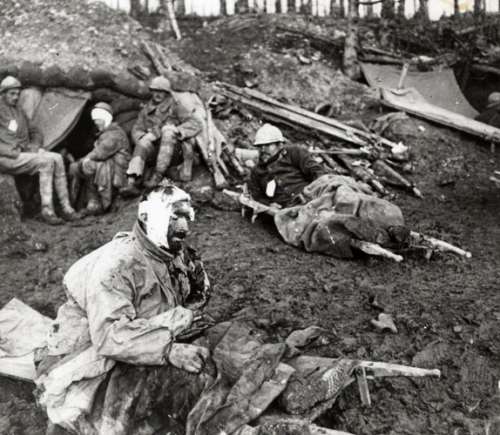

Proposition #4: Europe had expected a short war, and actually got one when the Schlieffen plan offensive bogged down 30 miles outside of Paris on the Marne River in mid-September 1914. Within three months, the Western Front had formed and coagulated into blood and mud——a ghastly 400 mile corridor of senseless carnage, unspeakable slaughter and incessant military stupidity that stretched from the Flanders coast across Belgium and northern France to the Swiss frontier.

The next four years witnessed an undulating line of trenches, barbed wire entanglements, tunnels, artillery emplacements and shell-pocked scorched earth that rarely moved more than a few miles in either direction, and which ultimately claimed more than 4 million casualties on the Allied side and 3.5 million on the German side.

The next four years witnessed an undulating line of trenches, barbed wire entanglements, tunnels, artillery emplacements and shell-pocked scorched earth that rarely moved more than a few miles in either direction, and which ultimately claimed more than 4 million casualties on the Allied side and 3.5 million on the German side.

If there was any doubt that Wilson’s catastrophic intervention converted a war of attrition, stalemate and eventual mutual exhaustion into Pyrrhic victory for the allies, it was memorialized in four developments during 1916.

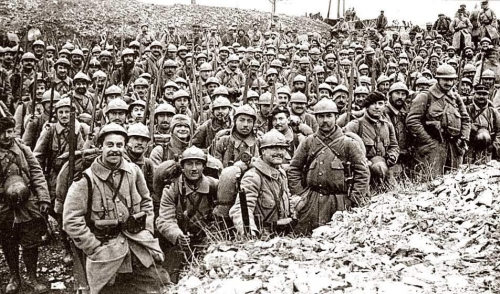

In the first, the Germans wagered everything on a massive offensive designed to overrun the fortresses of Verdun——the historic defensive battlements on France’s northeast border that had stood since Roman times, and which had been massively reinforced after the France’s humiliating defeat in Franco-Prussian War of 1870.

But notwithstanding the mobilization of 100 divisions, the greatest artillery bombardment campaign every recorded until then, and repeated infantry offensives from February through November that resulted in upwards of 400,000 German casualties, the Verdun offensive failed.

The second event was its mirror image—-the massive British and French offensive known as the battle of the Somme, which commenced with equally destructive artillery barrages on July 1, 1916 and then for three month sent waves of infantry into the maws of German machine guns and artillery. It too ended in colossal failure, but only after more than 600,000 English and French casualties including a quarter million dead.

In between these bloodbaths, the stalemate was reinforced by the naval showdown at Jutland that cost the British far more sunken ships and drowned sailors than the Germans, but also caused the Germans to retire their surface fleet to port and never again challenge the Royal Navy in open water combat.

Finally, by year-end 1916 the German generals who had destroyed the Russian armies in the East with only a tiny one-ninth fraction of the German army—Generals Hindenburg and Ludendorff —were given command of the Western Front. Presently, they radically changed Germany’s war strategy by recognizing that the growing allied superiority in manpower, owing to the British homeland draft of 1916 and mobilization of forces from throughout the empire, made a German offensive breakthrough will nigh impossible.

The result was the Hindenburg Line—a military marvel based on a checkerboard array of hardened pillbox machine gunners and maneuver forces rather than mass infantry on the front lines, and an intricate labyrinth of highly engineered tunnels, deep earth shelters, rail connections, heavy artillery and flexible reserves in the rear. It was also augmented by the transfer of Germany’s eastern armies to the western front—-giving it 200 divisions and 4 million men on the Hindenburg Line.

This precluded any hope of Entente victory. By 1917 there were not enough able-bodied draft age men left in France and England to overcome the Hindenburg Line, which, in turn, was designed to bleed white the entente armies led by butchers like Generals Haig and Joffre until their governments sued for peace.

Thus, with the Russian army’s disintegration in the east and the stalemate frozen indefinitely in the west by early 1917, it was only a matter of months before mutinies among the French lines, demoralization in London, mass starvation and privation in Germany and bankruptcy all around would have led to a peace of exhaustion and a European-wide political revolt against the war makers.

Wilson’s intervention thus did not remake the world. But it did radically re-channel the contours of 20th century history. And, as they say, not in a good way.

Proposition #5: Wilson’s epochal error not only produced the abomination of Versailles and all its progeny, but also the transformation of the Federal Reserve from a passive “banker’s bank” to an interventionist central bank knee-deep in Wall Street, government finance and macroeconomic management.

This, too, was a crucial historical hinge point because Carter Glass’ 1913 act forbid the new Reserve banks to even own government bonds; empowered them only to passively discount for cash good commercial credits and receivables brought to the rediscount window by member banks; and contemplated no open market interventions in debt markets or any remit with respect to GDP growth, jobs, inflation, housing or all the rest of modern day monetary central planning targets.

This, too, was a crucial historical hinge point because Carter Glass’ 1913 act forbid the new Reserve banks to even own government bonds; empowered them only to passively discount for cash good commercial credits and receivables brought to the rediscount window by member banks; and contemplated no open market interventions in debt markets or any remit with respect to GDP growth, jobs, inflation, housing or all the rest of modern day monetary central planning targets.

In fact, Carter Glass’ “banker’s bank” didn’t care whether the growth rate was positive 4%, negative 4% or anything in-between; its modest job was to channel liquidity into the banking system in response to the ebb and flow of commerce and production.

Jobs, growth and prosperity were to remain the unplanned outcome of millions of producers, consumers, investors, savers, entrepreneurs and speculators operating on the free market, not the business of the state.

But Wilson’s war took the national debt from about $1 billion or $11 per capita—–a level which had been maintained since the Battle of Gettysburg—-to $27 billion, including upwards of $10 billion re-loaned to the allies to enable them to continue the war. There is not a chance that this massive eruption of Federal borrowing could have been financed out of domestic savings in the private market.

So the Fed charter was changed owing to the exigencies of war to permit it to own government debt and to discount private loans collateralized by Treasury paper.

In due course, the famous and massive Liberty Bond drives became a glorified Ponzi scheme. Patriotic Americans borrowed money from their banks and pledged their war bonds; the banks borrowed money from the Fed, and re-pledged their customer’s collateral. The Reserve banks, in turn, created the billions they loaned to the commercial banks out of thin air, thereby pegging interest rates low for the duration of the war.

When Wilson was done saving the world, America had an interventionist central bank schooled in the art of interest rate pegging and rampant expansion of fiat credit not anchored in the real bills of commerce and trade; and its incipient Warfare and Welfare states had an agency of public debt monetization that could permit massive government spending without the inconvenience of high taxes on the people or the crowding out of business investment by high interest rates on the private market for savings.

Proposition # 6: By prolonging the war and massively increasing the level of debt and money printing on all sides, Wilson’s folly prevented a proper post-war resumption of the classical gold standard at the pre-war parities.

This failure of resumption, in turn, paved the way for the breakdown of monetary order and world trade in 1931—–a break which turned a standard post-war economic cleansing into the Great Depression, and a decade of protectionism, beggar-thy-neighbor currency manipulation and ultimately rearmament and statist dirigisme.

In essence, the English and French governments had raised billions from their citizens on the solemn promise that it would be repaid at the pre-war parities; that the war bonds were money good in gold.

But the combatant governments had printed too much fiat currency and inflation during the war, and through domestic regimentation, heavy taxation and unfathomable combat destruction of economic life in northern France had drastically impaired their private economies.

Accordingly, under Churchill’s foolish leadership England re-pegged to gold at the old parity in 1925, but had no political will or capacity to reduce bloated war-time wages, costs and prices in a commensurate manner, or to live with the austerity and shrunken living standards that honest liquidation of its war debts required.

At the same time, France ended up betraying its war time lenders, and re-pegged the Franc two years later at a drastically depreciated level. This resulted in a spurt of beggar-thy-neighbor prosperity and the accumulation of pound sterling claims that would eventually blow-up the London money market and the sterling based “gold exchange standard” that the Bank of England and British Treasury had peddled as a poor man’s way back on gold.

Yet under this “gold lite” contraption, France, Holland, Sweden and other surplus countries accumulated huge amounts of sterling liabilities in lieu of settling their accounts in bullion—–that is, they loaned billions to the British. They did this on the promise and the confidence that the pound sterling would remain at $4.87 per dollar come hell or high water—-just as it had for 200 years of peacetime before.

Yet under this “gold lite” contraption, France, Holland, Sweden and other surplus countries accumulated huge amounts of sterling liabilities in lieu of settling their accounts in bullion—–that is, they loaned billions to the British. They did this on the promise and the confidence that the pound sterling would remain at $4.87 per dollar come hell or high water—-just as it had for 200 years of peacetime before.

But British politicians betrayed their promises and their central bank creditors September 1931 by suspending redemption and floating the pound——-shattering the parity and causing the decade-long struggle for resumption of an honest gold standard to fail. Depressionary contraction of world trade, capital flows and capitalist enterprise inherently followed.

Proposition # 7: By turning America overnight into the granary, arsenal and banker of the Entente, the US economy was distorted, bloated and deformed into a giant, but unstable and unsustainable global exporter and creditor.

During the war years, for example, US exports increased by 4X and GDP soared from $40 billion to $90 billion. Incomes and land prices soared in the farm belt, and steel, chemical, machinery, munitions and ship construction boomed like never before—–in substantial part because Uncle Sam essentially provided vendor finance to the bankrupt allies in desperate need of both military and civilian goods.

Under classic rules, there should have been a nasty correction after the war—-as the world got back to honest money and sound finance. But it didn’t happen because the newly unleashed Fed fueled an incredible boom on Wall Street and a massive junk bond market in foreign loans.

In today economic scale, the latter amounted to upwards of $2 trillion and, in effect, kept the war boom in exports and capital spending going right up until 1929. Accordingly, the great collapse of 1929-1932 was not a mysterious failure of capitalism; it was the delayed liquidation of Wilson’s war boom.

After the crash, exports and capital spending plunged by 80% when the foreign junk bond binge ended in the face of massive defaults abroad; and that, in turn, led to a traumatic liquidation of industrial inventories and a collapse of credit fueled purchases of consumer durables like refrigerators and autos. The latter, for example, dropped from 5 million to 1.5 million units per year after 1929.

Proposition # 8: In short, the Great Depression was a unique historical event owing to the vast financial deformations of the Great War——deformations which were drastically exaggerated by its prolongation from Wilson’s intervention and the massive credit expansion unleashed by the Fed and Bank of England during and after the war.

Stated differently, the trauma of the 1930s was not the result of the inherent flaws or purported cyclical instabilities of free market capitalism; it was, instead, the delayed legacy of the financial carnage of the Great War and the failed 1920s efforts to restore the liberal order of sound money, open trade and unimpeded money and capital flows.

But this trauma was thoroughly misunderstood, and therefore did give rise to the curse of Keynesian economics and did unleash the politicians to meddle in virtually every aspect of economic life, culminating in the statist and crony capitalist dystopia that has emerged in this century.

Needless to say, that is Thomas Woodrow Wilson’s worst sin of all.

Reprinted with permission from David Stockman’s Corner.

The Best of David Stockman

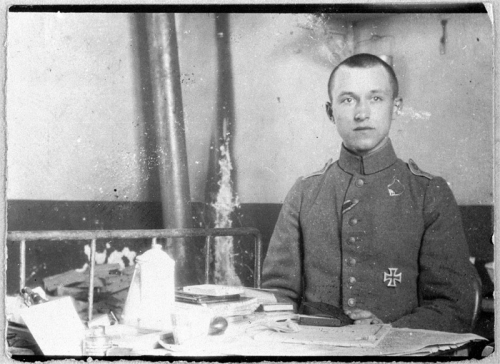

Michel Bernard, auteur de Visages de Verdun (Perrin) a exprimé le malheur qui a frappé tant de familles: «Il y a eu tellement de tués, mutilés et prisonniers, à Verdun et ailleurs, qu'en France comme en Allemagne, pour compléter les effectifs, il fallut avancer l'appel de la classe à mobiliser. La République et l'Empire incorporaient les fils de ceux tombés en 14. Beaucoup n'avaient pas dix-neuf ans, leurs joues étaient rondes et lisses sous le casque. Sans rien dire, ils montèrent aux créneaux du pays. Les femmes, lorsque le maire traversait la cour de la ferme, ne savaient pas pour qui, le fils ou le mari, leur cœur saisi allait se briser l'instant d'après.»

Michel Bernard, auteur de Visages de Verdun (Perrin) a exprimé le malheur qui a frappé tant de familles: «Il y a eu tellement de tués, mutilés et prisonniers, à Verdun et ailleurs, qu'en France comme en Allemagne, pour compléter les effectifs, il fallut avancer l'appel de la classe à mobiliser. La République et l'Empire incorporaient les fils de ceux tombés en 14. Beaucoup n'avaient pas dix-neuf ans, leurs joues étaient rondes et lisses sous le casque. Sans rien dire, ils montèrent aux créneaux du pays. Les femmes, lorsque le maire traversait la cour de la ferme, ne savaient pas pour qui, le fils ou le mari, leur cœur saisi allait se briser l'instant d'après.»

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

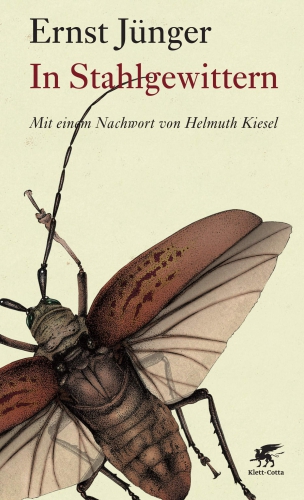

Le lecteur qui, comme moi, viendrait à peine d'achever la lecture de

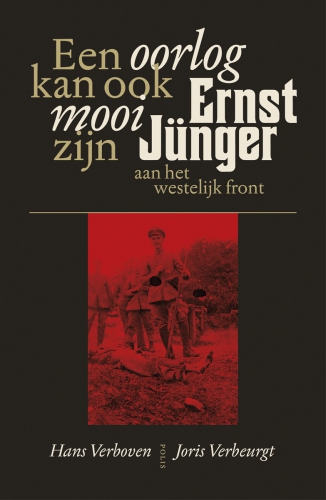

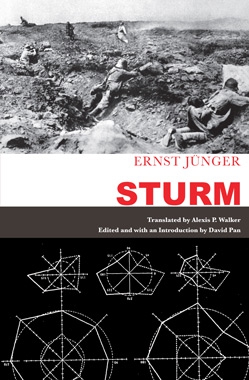

Le lecteur qui, comme moi, viendrait à peine d'achever la lecture de  La guerre est étrange, du moins certaines de ses phases. Nous pourrions dire d'elle qu'elle est l'étrangeté même, le tout autre, le plus souvent démoniaque, parfois la déhiscence d'un mystérieux au-delà du bien et du mal et pourtant, l'homme, toujours l'homme réduit à de la chair à canon, des cadavres horriblement torturés ou bien des guerriers impavides et courageux, est au centre du théâtre des opérations, au sens métaphysique et même religieux que nous pourrions donner à cette expression, comme si l'expérience de la Grande Guerre était comparable à la scène des vieux mystères du Moyen Âge : le boqueteau 125, bien connu des lecteurs de Jünger, «n'était jamais tenu que par quelques hommes, mais il prolongeait sa résistance, et c'est ainsi qu'il devenait, visible au loin dans ce paysage de mort, un exemple de ce que même le plus colossal affrontement n'est jamais que la balance où l'on pèse, aujourd'hui comme toujours, le poids de l'homme» (p. 349).

La guerre est étrange, du moins certaines de ses phases. Nous pourrions dire d'elle qu'elle est l'étrangeté même, le tout autre, le plus souvent démoniaque, parfois la déhiscence d'un mystérieux au-delà du bien et du mal et pourtant, l'homme, toujours l'homme réduit à de la chair à canon, des cadavres horriblement torturés ou bien des guerriers impavides et courageux, est au centre du théâtre des opérations, au sens métaphysique et même religieux que nous pourrions donner à cette expression, comme si l'expérience de la Grande Guerre était comparable à la scène des vieux mystères du Moyen Âge : le boqueteau 125, bien connu des lecteurs de Jünger, «n'était jamais tenu que par quelques hommes, mais il prolongeait sa résistance, et c'est ainsi qu'il devenait, visible au loin dans ce paysage de mort, un exemple de ce que même le plus colossal affrontement n'est jamais que la balance où l'on pèse, aujourd'hui comme toujours, le poids de l'homme» (p. 349). L'expérience du combat, surtout lorsqu'elle a lieu dans un théâtre des opérations où se déchaîne la Machine, surtout lorsque approche une «bataille telle que le monde n'en avait encore jamais vue (p. 121, j'ajoute le e manquant dans le texte), est la certitude de pénétrer dans un monde qui n'est pas celui, qui ne peut être celui de notre expérience quotidienne. Plus d'une fois, Ernst Jünger affirme ainsi qu'il a pu estimer se trouver dans une terre maudite (cf. p. 273) peuplée de démons, où il «errait comme sur un immense tas de décombres au-delà des bords du monde connu» (p. 151), terre maudite dont il remarque «la méchanceté spectrale» (p. 161) ou bien comparable à quelque contrée «des premiers âges» (p. 155), en bref, cette zone élémentaire dont j'ai parlé plus haut.

L'expérience du combat, surtout lorsqu'elle a lieu dans un théâtre des opérations où se déchaîne la Machine, surtout lorsque approche une «bataille telle que le monde n'en avait encore jamais vue (p. 121, j'ajoute le e manquant dans le texte), est la certitude de pénétrer dans un monde qui n'est pas celui, qui ne peut être celui de notre expérience quotidienne. Plus d'une fois, Ernst Jünger affirme ainsi qu'il a pu estimer se trouver dans une terre maudite (cf. p. 273) peuplée de démons, où il «errait comme sur un immense tas de décombres au-delà des bords du monde connu» (p. 151), terre maudite dont il remarque «la méchanceté spectrale» (p. 161) ou bien comparable à quelque contrée «des premiers âges» (p. 155), en bref, cette zone élémentaire dont j'ai parlé plus haut.  En 1915, Maurice Genevoix, jeune lieutenant de l'armée française, échappe de justesse à la mort. On est à Verdun, sur le front des Eparges. Choqué, meurtri, révolté, mais nourri par la beauté de ses hommes, leur bravoure, leurs souffrances, leurs doutes, leurs peurs, il n'aura de cesse toute sa vie de chanter un hymne à la vie, jailli du fond des tranchées boueuses.

En 1915, Maurice Genevoix, jeune lieutenant de l'armée française, échappe de justesse à la mort. On est à Verdun, sur le front des Eparges. Choqué, meurtri, révolté, mais nourri par la beauté de ses hommes, leur bravoure, leurs souffrances, leurs doutes, leurs peurs, il n'aura de cesse toute sa vie de chanter un hymne à la vie, jailli du fond des tranchées boueuses.

Fabrice Dutilleul : En cette période de « centenaire » ne peut-on considérer 1914-1918 comme un sujet aujourd’hui rebattu ?

Fabrice Dutilleul : En cette période de « centenaire » ne peut-on considérer 1914-1918 comme un sujet aujourd’hui rebattu ?

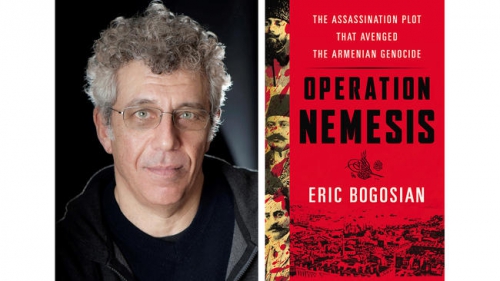

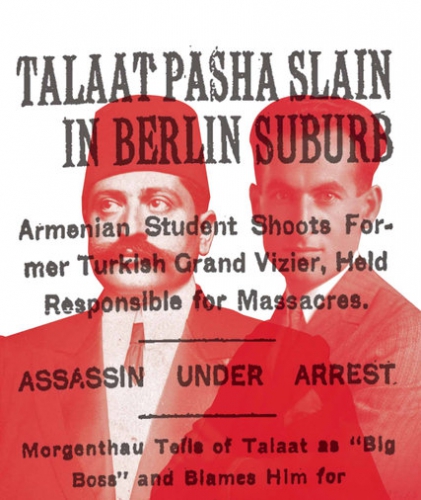

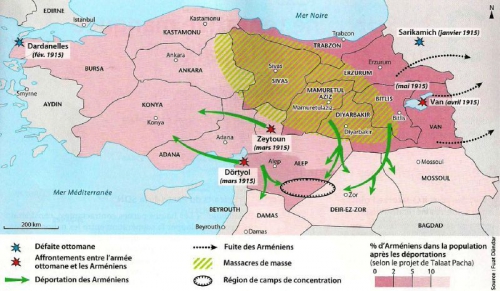

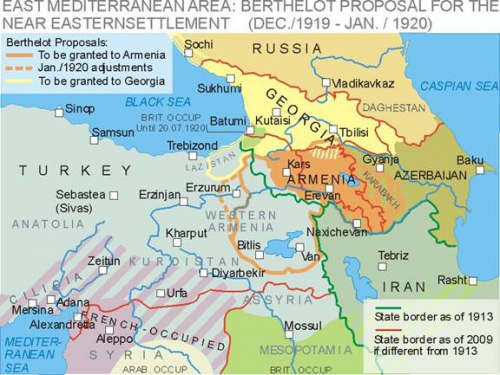

Christian soldiers — who, thanks to their new constitutional equal rights, could now serve in the military — were disarmed and put in work battalions, after which they were worked to death or slaughtered outright. On April 24, 1915, the Armenian community was decapitated. Some 250 prominent Armenians in Constantinople were arrested and subsequently murdered. In the Armenian homelands in the East, the genocide took place under the pretext of deportation and resettlement. Armenians packed and cataloged their valuables, handed over assets, and were marched out of their towns, where they were plundered and massacred, often with sickening Oriental sadism. Those who were not killed outright were marched to desert internment camps where they perished through disease, hunger, and violence. Between 800,000 and 1.4 million Armenians died, as well as more than half a million Greeks and Assyrians. Hundreds of thousands became refugees. By the end of the war, the Ottoman Empire had virtually eliminated its Armenian population.

Christian soldiers — who, thanks to their new constitutional equal rights, could now serve in the military — were disarmed and put in work battalions, after which they were worked to death or slaughtered outright. On April 24, 1915, the Armenian community was decapitated. Some 250 prominent Armenians in Constantinople were arrested and subsequently murdered. In the Armenian homelands in the East, the genocide took place under the pretext of deportation and resettlement. Armenians packed and cataloged their valuables, handed over assets, and were marched out of their towns, where they were plundered and massacred, often with sickening Oriental sadism. Those who were not killed outright were marched to desert internment camps where they perished through disease, hunger, and violence. Between 800,000 and 1.4 million Armenians died, as well as more than half a million Greeks and Assyrians. Hundreds of thousands became refugees. By the end of the war, the Ottoman Empire had virtually eliminated its Armenian population.

Thomas Edward Lawrence était farouchement hostile à la parution de son vivant des mémoires et comptes-rendus de ses aventures et opérations militaires conduites en Arabie entre 1916 et 1918. Il fit imprimer, en 1922, une édition privée qui circula dans un cercle très restreint. Lawrence estimait que certains passages des Sept Piliers étaient trop personnels, voire compromettants. Il ne souhaitait pas non plus embarrasser ses supérieurs hiérarchiques de la Royal Air Force : l’ancien colonel, héros de guerre de notoriété internationale, était alors devenu à sa demande un simple subalterne engagé sous un pseudonyme.

Thomas Edward Lawrence était farouchement hostile à la parution de son vivant des mémoires et comptes-rendus de ses aventures et opérations militaires conduites en Arabie entre 1916 et 1918. Il fit imprimer, en 1922, une édition privée qui circula dans un cercle très restreint. Lawrence estimait que certains passages des Sept Piliers étaient trop personnels, voire compromettants. Il ne souhaitait pas non plus embarrasser ses supérieurs hiérarchiques de la Royal Air Force : l’ancien colonel, héros de guerre de notoriété internationale, était alors devenu à sa demande un simple subalterne engagé sous un pseudonyme.

En estos artículos, que muestran la obsesiva actividad proselitista del autor, no nos encontramos con el Jünger elogiado por Hermann Hesse o H. G. Gadamer, con el ensayista profundo, el novelista imaginativo o el observador preciso, sino con el agitador político que lanza sin ambages su mensaje subversivo. No obstante, en estos escritos también se puede comprobar cierta evolución temática e intelectual. En los primeros textos se ocupa principalmente de la experiencia guerrera, del valor del sacrificio y de la sangre como cemento de una nueva sociedad, a lo que se une un profundo odio a la burguesía y a la República de Weimar. Jünger consideraba que en su generación había surgido un nuevo 'tipo humano', forjado en la guerra de material y de trincheras, a quien, a su vez, correspondía forjar un nuevo mundo: 'Como somos los auténticos, verdaderos e implacables enemigos del burgués, nos divierte su descomposición. Pero nosotros no somos burgueses, somos hijos de guerras y de enfrentamientos civiles...'. Inspirándose en Nietzsche, Spengler y Sorel, y haciendo suyo el pathos del futurismo italiano, Jünger ensalza el odio y la destrucción como elementos creativos: 'La verdadera voluntad de lucha, sin embargo, el odio verdadero, se alegra de todo lo que destruye a su contrario. La destrucción es el único instrumento que parece adecuado en las actuales circunstancias'. En estos pasajes, el escritor adopta un nihilismo heroico que convierte la violencia en un fin en sí mismo, en una experiencia mística del combatiente que debe continuar su lucha en la sociedad civil. En ellos desarrolla una estética pura de la violencia que se mueve en un vacío ético y que, supuestamente, según el autor, debería generar nuevos valores.

En estos artículos, que muestran la obsesiva actividad proselitista del autor, no nos encontramos con el Jünger elogiado por Hermann Hesse o H. G. Gadamer, con el ensayista profundo, el novelista imaginativo o el observador preciso, sino con el agitador político que lanza sin ambages su mensaje subversivo. No obstante, en estos escritos también se puede comprobar cierta evolución temática e intelectual. En los primeros textos se ocupa principalmente de la experiencia guerrera, del valor del sacrificio y de la sangre como cemento de una nueva sociedad, a lo que se une un profundo odio a la burguesía y a la República de Weimar. Jünger consideraba que en su generación había surgido un nuevo 'tipo humano', forjado en la guerra de material y de trincheras, a quien, a su vez, correspondía forjar un nuevo mundo: 'Como somos los auténticos, verdaderos e implacables enemigos del burgués, nos divierte su descomposición. Pero nosotros no somos burgueses, somos hijos de guerras y de enfrentamientos civiles...'. Inspirándose en Nietzsche, Spengler y Sorel, y haciendo suyo el pathos del futurismo italiano, Jünger ensalza el odio y la destrucción como elementos creativos: 'La verdadera voluntad de lucha, sin embargo, el odio verdadero, se alegra de todo lo que destruye a su contrario. La destrucción es el único instrumento que parece adecuado en las actuales circunstancias'. En estos pasajes, el escritor adopta un nihilismo heroico que convierte la violencia en un fin en sí mismo, en una experiencia mística del combatiente que debe continuar su lucha en la sociedad civil. En ellos desarrolla una estética pura de la violencia que se mueve en un vacío ético y que, supuestamente, según el autor, debería generar nuevos valores.  En el terreno ideológico, los artículos reflejan una visión particular y nebulosa que no llega a identificarse con ninguna de las ideologías dominantes. Sus rasgos principales son, en su vertiente negativa, un profundo sentimiento antidemocrático y antipacifista, así como un fuerte rechazo de las instituciones, excluyendo al ejército como encarnación de la idea prusiana. Su odio a la República de Weimar es manifiesto; una República, si bien es cierto, que se ha definido con frecuencia como la 'democracia sin demócratas' y que era el blanco favorito del desprecio de la mayoría de los intelectuales. Aunque Jünger se confiesa nacionalista, en concreto 'nacionalista de la acción', no asocia el concepto con una forma política concreta, más bien se limita a describir vagamente modelos utópicos o retóricos que encontrarán un desarrollo más maduro en su libro El trabajador. Armin Mohler empleó el término 'revolución conservadora' para explicar esta posición política, pero Jünger también se acercó al nacionalismo de izquierdas de un Niekisch e incluso colaboró en su revista Der Widerstand, prohibida con posterioridad por los nacionalsocialistas. La impresión que recibimos es que Jünger estaba obsesionado con una revolución, viniese de donde viniese, siempre que fuese nacional. En sus escritos solía dirigirse a 'los nacionalistas, los soldados del frente y los trabajadores'. Este empeño revolucionario fue el que le acercó al nacionalsocialismo en los primeros años del movimiento: 'La verdadera revolución aún no se ha producido, pero se aproxima irresistiblemente. No es ninguna reacción, sino una revolución auténtica con todos sus rasgos y sus manifestaciones; su idea es la popular, afilada hasta un extremo desconocido; su bandera es la cruz gamada; su forma de expresión, la concentración de la voluntad en un único punto: la dictadura. Sustituirá la palabra por la acción, la tinta por la sangre, la frase por el sacrificio, la pluma por la espada'.

En el terreno ideológico, los artículos reflejan una visión particular y nebulosa que no llega a identificarse con ninguna de las ideologías dominantes. Sus rasgos principales son, en su vertiente negativa, un profundo sentimiento antidemocrático y antipacifista, así como un fuerte rechazo de las instituciones, excluyendo al ejército como encarnación de la idea prusiana. Su odio a la República de Weimar es manifiesto; una República, si bien es cierto, que se ha definido con frecuencia como la 'democracia sin demócratas' y que era el blanco favorito del desprecio de la mayoría de los intelectuales. Aunque Jünger se confiesa nacionalista, en concreto 'nacionalista de la acción', no asocia el concepto con una forma política concreta, más bien se limita a describir vagamente modelos utópicos o retóricos que encontrarán un desarrollo más maduro en su libro El trabajador. Armin Mohler empleó el término 'revolución conservadora' para explicar esta posición política, pero Jünger también se acercó al nacionalismo de izquierdas de un Niekisch e incluso colaboró en su revista Der Widerstand, prohibida con posterioridad por los nacionalsocialistas. La impresión que recibimos es que Jünger estaba obsesionado con una revolución, viniese de donde viniese, siempre que fuese nacional. En sus escritos solía dirigirse a 'los nacionalistas, los soldados del frente y los trabajadores'. Este empeño revolucionario fue el que le acercó al nacionalsocialismo en los primeros años del movimiento: 'La verdadera revolución aún no se ha producido, pero se aproxima irresistiblemente. No es ninguna reacción, sino una revolución auténtica con todos sus rasgos y sus manifestaciones; su idea es la popular, afilada hasta un extremo desconocido; su bandera es la cruz gamada; su forma de expresión, la concentración de la voluntad en un único punto: la dictadura. Sustituirá la palabra por la acción, la tinta por la sangre, la frase por el sacrificio, la pluma por la espada'.

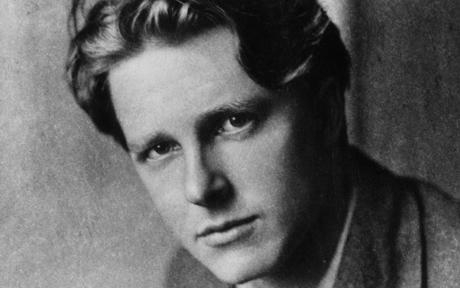

Il y a cent ans mourait en Méditerranée sur le chemin des Dardanelles, le 23 avril 1915, le « plus beau jeune homme de l'Angleterre » selon les propos de Yeats, l'un de ses plus grands poètes, Rupert Brooke. Tout écolier anglais a récité à l'école ou le 11 novembre, devant le monument aux morts de son village les célèbres vers du

Il y a cent ans mourait en Méditerranée sur le chemin des Dardanelles, le 23 avril 1915, le « plus beau jeune homme de l'Angleterre » selon les propos de Yeats, l'un de ses plus grands poètes, Rupert Brooke. Tout écolier anglais a récité à l'école ou le 11 novembre, devant le monument aux morts de son village les célèbres vers du  Contrairement aux écrivains de Bloomsbury qui opteront pour l'objection de conscience, Brooke entre sur recommandation de Churchill en personne dans une division de la Marine britannique et comme officier, il prendra part à l'expédition catastrophique d'Anvers d'octobre 1914 en Belgique. En Février 1915, après une courte permission en Angleterre où il écrira ses cinq sonnets de guerre qui le rendront célèbre pour l'éternité, il s'embarque pour les Dardanelles mais

Contrairement aux écrivains de Bloomsbury qui opteront pour l'objection de conscience, Brooke entre sur recommandation de Churchill en personne dans une division de la Marine britannique et comme officier, il prendra part à l'expédition catastrophique d'Anvers d'octobre 1914 en Belgique. En Février 1915, après une courte permission en Angleterre où il écrira ses cinq sonnets de guerre qui le rendront célèbre pour l'éternité, il s'embarque pour les Dardanelles mais

Pierre Drieu la Rochelle n’a éjaculé qu’une seule fois dans sa vie : c’était le 23 août 1914, lors d’une chaude journée de guerre dans la plaine de Charleroi. Ce jour-là, le caporal de 21 ans vit sa première épreuve du feu. Soudain, au milieu de l’affrontement, il se lève, comme s’il n’avait plus peur de la mort, charge son fusil et entraîne plusieurs camarades. L’enivrement que lui procure la sensation d’être devenu le chef qu’il a toujours rêvé d’incarner est comme un orgasme sexuel. « Alors, tout d’un coup, il s’est produit quelque chose d’extraordinaire. Je m’étais levé, levé entre les morts, entre les larves. […] Tout d’un coup, je me connaissais, je connaissais ma vie. C’était donc ma vie, cet ébat qui n’allait plus s’arrêter jamais »*, écrit-il dans La comédie de Charleroi (1934) qui rassemble, sous forme de nouvelles, ses expériences de la Grande Guerre.

Pierre Drieu la Rochelle n’a éjaculé qu’une seule fois dans sa vie : c’était le 23 août 1914, lors d’une chaude journée de guerre dans la plaine de Charleroi. Ce jour-là, le caporal de 21 ans vit sa première épreuve du feu. Soudain, au milieu de l’affrontement, il se lève, comme s’il n’avait plus peur de la mort, charge son fusil et entraîne plusieurs camarades. L’enivrement que lui procure la sensation d’être devenu le chef qu’il a toujours rêvé d’incarner est comme un orgasme sexuel. « Alors, tout d’un coup, il s’est produit quelque chose d’extraordinaire. Je m’étais levé, levé entre les morts, entre les larves. […] Tout d’un coup, je me connaissais, je connaissais ma vie. C’était donc ma vie, cet ébat qui n’allait plus s’arrêter jamais »*, écrit-il dans La comédie de Charleroi (1934) qui rassemble, sous forme de nouvelles, ses expériences de la Grande Guerre.

Commentators marked World War I’s centenary last year with cloudy references to its “

Commentators marked World War I’s centenary last year with cloudy references to its “ For German survivors, withered by hunger, life reduced to a series of grim alternatives. Lina Richter

For German survivors, withered by hunger, life reduced to a series of grim alternatives. Lina Richter  Che cosa sta succedendo in Siria e in Iraq? Semplice: sta succedendo che uno dei principali alleati degli Stati Uniti nella regione – l’Emirato del Qatar – stia finanziando ed armando un esercito di terroristi che vuole cancellare Iraq, Siria, Libano e Giordania, ed al loro posto creare un impero clericale – il Califfato – ispirato ad una interpretazione fondamentalista dell’Islamismo nella sua versione sunnita.

Che cosa sta succedendo in Siria e in Iraq? Semplice: sta succedendo che uno dei principali alleati degli Stati Uniti nella regione – l’Emirato del Qatar – stia finanziando ed armando un esercito di terroristi che vuole cancellare Iraq, Siria, Libano e Giordania, ed al loro posto creare un impero clericale – il Califfato – ispirato ad una interpretazione fondamentalista dell’Islamismo nella sua versione sunnita.

“La battaglia rientra nelle grandi passioni. [...] E’ un canto antico e tremendo, che risale all’alba dell’uomo: nessuno avrebbe mai pensato che fosse ancora così vivo in noi”. In questo scritto di guerra non manca nulla: il sangue, l’orrore, la trincea, l’eros, il coraggio, il fuoco, la paura… Questo per dare un’idea di ciò che aspetta il lettore che abbia il coraggio e la maturità di affrontare quest’opera rovente, che di certo non poteva non piacere ad un giovane nazional-socialista dei tempi. Perché Jünger è stato considerato, e forse è considerato ancora, un nazista. E’ vero che Hitler disse “Jünger non si tocca!” e lo protesse per ben due volte dalle grinfie di Göring che voleva la sua testa. Ma furono il rispetto per il soldato e lo scrittore di guerra che, con tutta probabilità, spinsero il Führer a perdonare a Jünger il suo comportamento. Ci si riferisce al suo antinazismo allegorico, aleggiante nel romanzo Sulle scogliere di marmo, e alla sua parte nella congiura capitanata da Stauffenberg che sfumò nel fallito attentato a Hitler, ben narrato nel film di Bryan Singer Operazione Valchiria. Scrisse un romanzo antinazista e partecipò all’attentato a Hitler, che mirava ad ucciderlo. Anche se in lui l’idea dell’uccisione del tiranno era indicice di mentalità rozza. Queste due cose stanno ben a sottolineare il fantomatico nazismo di cui fu accusato. Ma agli occhi stanchi e superficiali dei molti faciloni, è apparso così per molto tempo. È vero invece che i nazisti trassero, a piene mani, buona parte della loro cultura da alcuni scritti del grande soldato tedesco. Solo in seguito al premio Goethe, ottenuto nell’82, venne riabilitato ufficialmente come scrittore.

“La battaglia rientra nelle grandi passioni. [...] E’ un canto antico e tremendo, che risale all’alba dell’uomo: nessuno avrebbe mai pensato che fosse ancora così vivo in noi”. In questo scritto di guerra non manca nulla: il sangue, l’orrore, la trincea, l’eros, il coraggio, il fuoco, la paura… Questo per dare un’idea di ciò che aspetta il lettore che abbia il coraggio e la maturità di affrontare quest’opera rovente, che di certo non poteva non piacere ad un giovane nazional-socialista dei tempi. Perché Jünger è stato considerato, e forse è considerato ancora, un nazista. E’ vero che Hitler disse “Jünger non si tocca!” e lo protesse per ben due volte dalle grinfie di Göring che voleva la sua testa. Ma furono il rispetto per il soldato e lo scrittore di guerra che, con tutta probabilità, spinsero il Führer a perdonare a Jünger il suo comportamento. Ci si riferisce al suo antinazismo allegorico, aleggiante nel romanzo Sulle scogliere di marmo, e alla sua parte nella congiura capitanata da Stauffenberg che sfumò nel fallito attentato a Hitler, ben narrato nel film di Bryan Singer Operazione Valchiria. Scrisse un romanzo antinazista e partecipò all’attentato a Hitler, che mirava ad ucciderlo. Anche se in lui l’idea dell’uccisione del tiranno era indicice di mentalità rozza. Queste due cose stanno ben a sottolineare il fantomatico nazismo di cui fu accusato. Ma agli occhi stanchi e superficiali dei molti faciloni, è apparso così per molto tempo. È vero invece che i nazisti trassero, a piene mani, buona parte della loro cultura da alcuni scritti del grande soldato tedesco. Solo in seguito al premio Goethe, ottenuto nell’82, venne riabilitato ufficialmente come scrittore.

Na het uitbreken van de Eerste Wereldoorlog werd Lawrence, die Arabisch sprak, ingezet bij het organiseren van sabotage-acties tegen de bovengenoemde spoorweg. Het doel was om het Arabische schiereiland los te weken van het Ottomaanse Rijk. Om die reden was ook voorzien in een Arabische opstand. Daarvoor werd de meest agressieve en martiale stam uitgekozen, de Sauds. De Sauds waren aanhangers van het Wahabisme, een back-to-basics vorm van Islam, die zeer sober en orthodox was en beter pastte bij de woestijn dan bij het grootstedelijke leven in het Ottomaanse Rijk.

Na het uitbreken van de Eerste Wereldoorlog werd Lawrence, die Arabisch sprak, ingezet bij het organiseren van sabotage-acties tegen de bovengenoemde spoorweg. Het doel was om het Arabische schiereiland los te weken van het Ottomaanse Rijk. Om die reden was ook voorzien in een Arabische opstand. Daarvoor werd de meest agressieve en martiale stam uitgekozen, de Sauds. De Sauds waren aanhangers van het Wahabisme, een back-to-basics vorm van Islam, die zeer sober en orthodox was en beter pastte bij de woestijn dan bij het grootstedelijke leven in het Ottomaanse Rijk.

By so altering the course of history, Wilson’s war bankrupted Europe and midwifed 20th century totalitarianism in Russia and Germany.

By so altering the course of history, Wilson’s war bankrupted Europe and midwifed 20th century totalitarianism in Russia and Germany. Now, owing to Wilson’s fetid patrimony, we have the opposite: A world of the Warfare State, the Welfare State, Central Bank omnipotence and a crushing burden of private and public debts. That is, a thoroughgoing statist regime that is fundamentally inimical to capitalist prosperity, free market governance of economic life and the flourishing of private liberty and constitutional safeguards against the encroachments of the state.

Now, owing to Wilson’s fetid patrimony, we have the opposite: A world of the Warfare State, the Welfare State, Central Bank omnipotence and a crushing burden of private and public debts. That is, a thoroughgoing statist regime that is fundamentally inimical to capitalist prosperity, free market governance of economic life and the flourishing of private liberty and constitutional safeguards against the encroachments of the state. The next four years witnessed an undulating line of trenches, barbed wire entanglements, tunnels, artillery emplacements and shell-pocked scorched earth that rarely moved more than a few miles in either direction, and which ultimately claimed more than 4 million casualties on the Allied side and 3.5 million on the German side.

The next four years witnessed an undulating line of trenches, barbed wire entanglements, tunnels, artillery emplacements and shell-pocked scorched earth that rarely moved more than a few miles in either direction, and which ultimately claimed more than 4 million casualties on the Allied side and 3.5 million on the German side. This, too, was a crucial historical hinge point because Carter Glass’ 1913 act forbid the new Reserve banks to even own government bonds; empowered them only to passively discount for cash good commercial credits and receivables brought to the rediscount window by member banks; and contemplated no open market interventions in debt markets or any remit with respect to GDP growth, jobs, inflation, housing or all the rest of modern day monetary central planning targets.

This, too, was a crucial historical hinge point because Carter Glass’ 1913 act forbid the new Reserve banks to even own government bonds; empowered them only to passively discount for cash good commercial credits and receivables brought to the rediscount window by member banks; and contemplated no open market interventions in debt markets or any remit with respect to GDP growth, jobs, inflation, housing or all the rest of modern day monetary central planning targets. Yet under this “gold lite” contraption, France, Holland, Sweden and other surplus countries accumulated huge amounts of sterling liabilities in lieu of settling their accounts in bullion—–that is, they loaned billions to the British. They did this on the promise and the confidence that the pound sterling would remain at $4.87 per dollar come hell or high water—-just as it had for 200 years of peacetime before.

Yet under this “gold lite” contraption, France, Holland, Sweden and other surplus countries accumulated huge amounts of sterling liabilities in lieu of settling their accounts in bullion—–that is, they loaned billions to the British. They did this on the promise and the confidence that the pound sterling would remain at $4.87 per dollar come hell or high water—-just as it had for 200 years of peacetime before.

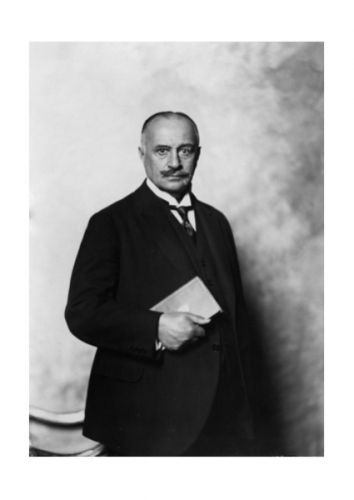

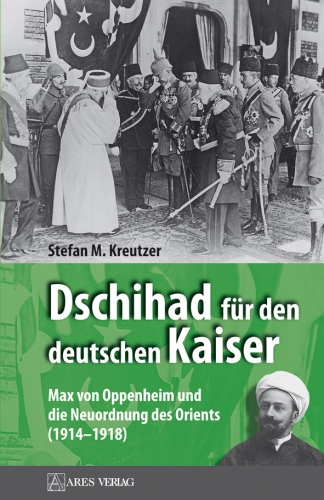

Er war gekleidet wie ein Beduine, sprach fließend Arabisch und pilgerte von Moschee zu Moschee. Im Sommer 1915 sorgte ein Deutscher im Nahen Osten und auf der arabischen Halbinsel für Aufsehen. Er propagierte den Heiligen Krieg gegen die ungläubigen Kolonialherren in Afrika und Asien - vor allem gegen die Briten. Er zog durch Syrien, Palästina, bereiste die Halbinsel Sinai und Nordwestarabien, ließ kaum einen Landstrich aus.

Er war gekleidet wie ein Beduine, sprach fließend Arabisch und pilgerte von Moschee zu Moschee. Im Sommer 1915 sorgte ein Deutscher im Nahen Osten und auf der arabischen Halbinsel für Aufsehen. Er propagierte den Heiligen Krieg gegen die ungläubigen Kolonialherren in Afrika und Asien - vor allem gegen die Briten. Er zog durch Syrien, Palästina, bereiste die Halbinsel Sinai und Nordwestarabien, ließ kaum einen Landstrich aus.  So reiste Oppenheim im Frühjahr 1915 nach Istanbul, um Scharif Husseins Sohn, Prinz Faisal, seine Pläne darzulegen. Oppenheims Geschenke nahm Faisal gern an: ein Automobil, ein Gewehr und viel Geld. Eine feste Zusage machte er nicht. Was Oppenheim vielleicht ahnte, aber nicht sicher wusste: Scharif Hussein war auch mit den Briten im Gespräch, die eine ganz ähnliche Strategie wie die Deutschen verfolgten. Um das deutsch-türkische Bündnis zu schwächen, wollten sie einen Aufstand der Araber gegen die Türken anzetteln, unter deren Joch die Araber schon weit länger litten als unter dem britischen.

So reiste Oppenheim im Frühjahr 1915 nach Istanbul, um Scharif Husseins Sohn, Prinz Faisal, seine Pläne darzulegen. Oppenheims Geschenke nahm Faisal gern an: ein Automobil, ein Gewehr und viel Geld. Eine feste Zusage machte er nicht. Was Oppenheim vielleicht ahnte, aber nicht sicher wusste: Scharif Hussein war auch mit den Briten im Gespräch, die eine ganz ähnliche Strategie wie die Deutschen verfolgten. Um das deutsch-türkische Bündnis zu schwächen, wollten sie einen Aufstand der Araber gegen die Türken anzetteln, unter deren Joch die Araber schon weit länger litten als unter dem britischen.